Kanazawa Station is one of Japan’s most aesthetically pleasing station buildings. The station’s architecture is all the more pleasing because it seems to perfectly blend modern style with a respect for tradition. When we look closely at Kanazawa station we can learn a lot about Kanazawa’s history, its respect for tradition, and its enterprising vision for the future.

From a distance the contours of Kanazawa Station resemble a samurai helmet

Table of Contents

The Sacred Gate

Probably the most striking part of Kanazawa Station is its massive wooden gate. People exiting the station are always impressed when they first see this large vermilion structure, and it looks even more impressive when viewed from the other side, opposite the station, with the huge glass dome of the plaza roof rising behind it. There is usually a small crowd of tourists and travelers gathered just in front of the gate taking memorial pictures. You could say that this gate has become a symbol of Kanazawa itself.

Kanazawa Station’s Tsuzumi-mon Gate

What is interesting about this gate is that it is built in the form of a traditional torii gate, and these gates usually stand at the entrance to a Japanese shrine. They are meant to mark the moment when you move between your ordinary day-to-day life and transition into a sacred space. Obviously putting a big red torii gate between the station and the city is very symbolic, but what exactly does it mean? Does it mean that the station is a sacred place, or that embarking on a journey is sacred? Or when we move through the gate into Kanazawa are we entering a sacred city? This city does, after all, have many, many temples, and historically the city was actually born from a revolutionary religious idea.

The Temple City

The teachings of the Buddhist leader Rennyo inspired a revolution

Back in the 15th century, a new branch of Buddhism became very popular in this region because it taught a sacred truth: that all people are equal. This teaching of equality inspired the local people to rise up and throw out their lords. They set up their own independent “Peasants’ Kingdom” which they ruled from a fortified temple on elevated ground. The temple was called Oyama Gobo and the city of Kanazawa grew up around it. After a century, this Buddhist kingdom fell and the temple was replaced by Kanazawa Castle, but Buddhist ideas and philosophy remained very important here. So perhaps the torii gate at the front of Kanazawa Station is partly a tribute to that religious origin.

The City of Culture

Very often in Japanese shrines, there is not just one gate, but a series of gates, and actually this is true of Kanazawa Station too.

Kanazawa Station’s concourse

In the station building’s central concourse you can see that the roof is supported by a series of wooden pillars joined at the top by wooden beams. Built from local cypress wood there are 12 of these gates with 24 pillars. Take a closer look at them and you will see embedded in each one a beautiful piece of art. These artworks represent Kanazawa’s heritage crafts of lacquerware, woodwork, and ceramics.

[Left] Wajima Urushi lacquerware by Fumio Mae, a living national treasure

[Right] Kutani-yaki porcelain by Kazunori Takegoshi

These crafts date from a long period of high artistic and cultural development in Kanazawa. In 1583, after the fall of the Peasants Kingdom, a general named Maeda Toshiie, was given control over the region. His family ruled from Kanazawa Castle for almost three centuries. During that time they invited many talented craftsmen and artists to work in Kanazawa and the city was transformed into a center of culture famed for its gold and silver leaf craftwork, lacquerware, ceramics, and silk. Noh theater and the geisha arts also flourished here at this time. You can see Noh represented in the torii gate at the front of the station. The two vertical pillars are shaped to resemble tsuzumi, a type of drum used in Noh theater, and that is why the gate is called the “Tsuzumi-mon” or “Tsuzumi Gate”.

The drum-like legs of the Tsuzumi-mon gate

You can find other traditional crafts such as yuzen silk, and washi paper, dotted around different parts of the station and even on the shinkansen platforms the tops of the pillars are decorated with gold leaf.

Gold topped pillars on the shinkansen platforms. Kanazawa today supplies 99% of Japan’s gold leaf

The period of Maeda rule is seen as Kanazawa’s golden age, but this came to an end in the 19th century when Japan opened its borders to the world. A period of dramatic social and political change followed, in which the Maeda family lost power and Kanazawa lost its regional influence. In the 1870s while other major cities underwent rapid industrialization, and were connected by an ever expanding network of railways, Kanazawa fell behind. In fact the railway didn’t arrive in Kanazawa until the end of the century.

The First Kanazawa Station

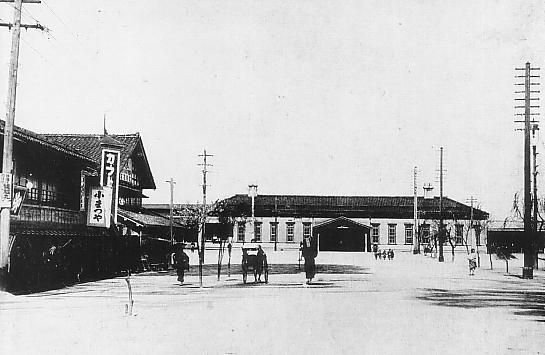

In 1898 the Hokuriku Rail Line was extended from its previous northern terminus in Fukui to the city of Kanazawa. The first Kanazawa Station was opened in April of 1898 to service this line. It was a one story wooden building of wood with a chimney at each end and waiting rooms which were lit by oil lamps at night. The station was built in a rather isolated area surrounded by fields. Where now we see a well ordered bus terminal and taxi rank, the very first passengers would have exited the building to an open plaza of bare earth and lines of rickshaw runners waiting to whisk them away into all parts of the city. The first taxi cabs didn’t appear here until 1920.

An early photograph of Kanazawa Station

The coming of the railway was greeted with much excitement in Kanazawa, because it brought with it the modern age and the promise of regional development both economically and culturally. Travel time between the northern Hokuriku area and central Japan was dramatically reduced, and local people would come with picnic boxes to view with wonder the arrival of the very latest technology – the steam train.

This scale model of the station in Ishikawa Prefectural History Museum was made using photographs and the original architectural plans

The first Kanazawa Station would serve the city for over 50 years. By the 1930s, the number of passengers had increased to the extent that people were calling for a new and bigger building. However, the beginning of war in China in 1937, and entry into World War II in 1941 meant that there simply wasn’t the manpower, or economic and material resources to replace the station. Waiting rooms were removed and minor additions and renovations were made here and there. This only helped a little to accommodate the large crowds who cheered as their young men went off to war, and who greeted the survivors when they returned.

Kanazawa Station in 1932

Kanazawa had no industry, so it was not bombed during the war and the station survived intact. By 1945 however, the old wooden building looked shabby and worn out, and local citizens felt it was no longer suitable as the gateway for the Hokuriku region’s major city. Overcrowding was also desperate, with an average of 28,300 passengers using the station each day; that is 14 times more than when the station first opened. Unfortunately though, the central government and the occupation forces had other priorities. Kanazawa was lucky to have a station at all. On the Tokaido Railway Line between Tokyo and Kobe, all the stations had been destroyed by Allied bombs. While these were reconstructed, Kanazawa had to wait. Finally, in 1950 the local governments of Kanazawa city and Ishikawa Prefecture, together with prominent local citizens came up with a plan.

The Second Kanazawa Station

The second Kanazawa Station was officially called “Kanazawa Minshu Eki” which means “Kanazawa People’s Station” because it was built with popular support. These minshu eki had begun to appear around the country as a way to revitalize local economies, and the local government in Kanazawa decided to follow their example. Basically local government with the support of local citizens would pay for the construction, and in return when the station was built, they could open shops and restaurants inside the station. Construction of the new station began in 1951 and was completed in 1953.

Kanazawa Station in 1963. Notice the tramlines in front

The second Kanazawa Station was a four story blockish building of concrete reinforced with steel. Though it may not look so sophisticated to our contemporary eyes, at the time it was a big step forward for Kanazawa as part of a wider plan to modernize the city.

By 1984 the station building has expanded and the tramlines have been replaced by buses

In the beginning there were just 44 shops in the building, but these increased with the addition of more space in the basement level. This involvement of local business in the development of the station, led to the station area becoming a major retail center. Today we see its legacy in the station’s Hyakubangai shopping mall, where national and international brand boutiques stand alongside branches of Kanazawa’s oldest traditional shops.

Shopping in Kanazawa Station today

The Contemporary Station

In the late 1990s it became clear that the Hokuriku Shinkansen Line would be extended to Kanazawa, and it became necessary to expand the facilities to accommodate new rail lines. An extensive rebuilding program began in 1998 which was completed in 2005. In place of the old utilitarian rectangular block, the new look station is a fine mix of sleek modern style and convenience with respectful nods to the past. In particular, the design of architect Ryuzo Shirae for the eastern façade, with its covered plaza and Tsuzumi-mon Gate has received several international awards.

The station has also been listed by Travel & Leisure Magazine as one of the “world’s most beautiful train stations”. The design is not only beautiful but smart. Kanazawa is prone to frequent rain and snowfall, but the massive dome of aluminium and glass that covers the station plaza offers practical shelter to passengers waiting for taxis and buses. Solar cells on the station roof also provide ecologically friendly energy.

Inside the “Motenashi Dome” over the station’s east plaza. “Motenashi” means “hospitality”

Kanazawa Station is just one of several innovative, contemporary buildings in the city. In 2004, one year before the station was completed, Kanazawa’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art was opened. This futuristic building resembling a giant spaceship houses several galleries of modern art and has become one of the city’s chief attractions. The nearby D. T. Suzuki Museum with its simple, minimalist water garden opened in 2011. At the same time the city still has a thriving traditional arts and crafts scene and this was recognized in 2009 by UNESCO who listed it on their Creative Cities network as a City of Crafts. The extension of the Hokuriku Shinkansen Line to Kanazawa in 2015, has made the city’s attractions, both old and new, ever more popular, as tourists can now travel from Tokyo in just 2 hours and 30 minutes. It seems fitting that the current station building is one that perfectly reflects a city looking both forward and back, and gives shelter to both modern and traditional design ideals.

Article and original photos by Michael Lambe. All rights reserved.